By Madalyn Johnson, Public Archaeology Intern

Rock imagery (more commonly referred to as rock art) is likely one of the first things you think of when you hear the word “archaeology”. Pictographs and petroglyphs — painted or carved figures on rock faces, respectively — are not only some of the more aesthetic things left behind by past peoples, but they also provide useful archaeological information; this is particularly true in the study of prehistoric Indigenous American shields.

Background

Across Western North America, prehistoric peoples made shields from organic materials such as plant fibers or buffalo hide. Being constructed this way made them particularly susceptible to decay over time, as organic materials are easily broken down by microorganisms in the earth, like bacteria or fungi. Consequently, very few physical examples of shields constructed and used before the ethnohistoric era (ca. 1850) have been encountered.

Prehistoric shields fall into two categories: hide shields and basketry shields.

The only hide shields ever recovered that pre-date the introduction of the horse to the Americas are three shields discovered in 1925 near Torrey, Utah by Ephraim Pectol (Figure 1); these three shields are now known as the “Pectol shields.” Constructed from a single layer of hide, the shields are “convex in cross-section and round in plan with dynamic painted geometric designs in red, green, and black — they originally ranged from about 78 to 96 cm in diameter.” (Jolie, 2022) The shields also have buckskin hide ties on their faces that would have been used to attach an arm strap or to attach adornments that could have been similar to feather and pendant attachments seen on ethnohistoric era shields.

Figure 1. Ephraim Pectol with a hide shield he discovered. Photo courtesy of J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

In addition, five basketry shields from the northern Southwest do exist in museum collections. Two of these basketry shields were recovered from the Aztec West Ruin site in Aztec, New Mexico, one from Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, one from the Cliff Palace site in Mesa Verde, Colorado, and one from the White House site in Canyon del Muerto (Figure 2).

These shields were constructed from coiled and stitched plant fibers and range in estimated size from 45 to 88 centimeters in diameter. One is likely to have been oval in shape, while the rest are largely circular. Four of these shields are painted with yellow, black, red, and/or white pigments in designs that range from geometric shapes to a figure that resembles a frog. Hide ties like those on the Pectol shields are also present on some of these basketry shields.

Figure 2. A painted basketry shield collected from the White House site in Canyon del Muerto, Arizona. Photo courtesy of Edward A. Jolie and the American Museum of Natural History.

While these shields are incredibly compelling and provide valuable archaeological information, they are few and far between; this poses a problem for archaeologists who want to understand the role shields played in their respective cultures. This is where rock imagery can be useful.

Shields take many forms in rock imagery. Some are simple circles, while others are elaborately decorated and connected to human figures.

Project Background

Shield iconography in rock imagery is widespread and can take many forms; some rock imagery shields are simple circles, while others are elaborately decorated and connected to an anthropomorphic, or human-like, figure. The reason why past peoples left behind such images will never be known for certain, but patterns in where they are found may yield some clues.

This project aimed to identify spatial patterns in shield iconography across Eastern Utah, focusing on patterns regarding types of shield imagery and where they were found, and describe them.

This project explored the distribution of shield figures across Eastern Utah, searching for spatial patterns in their placement.

Methods

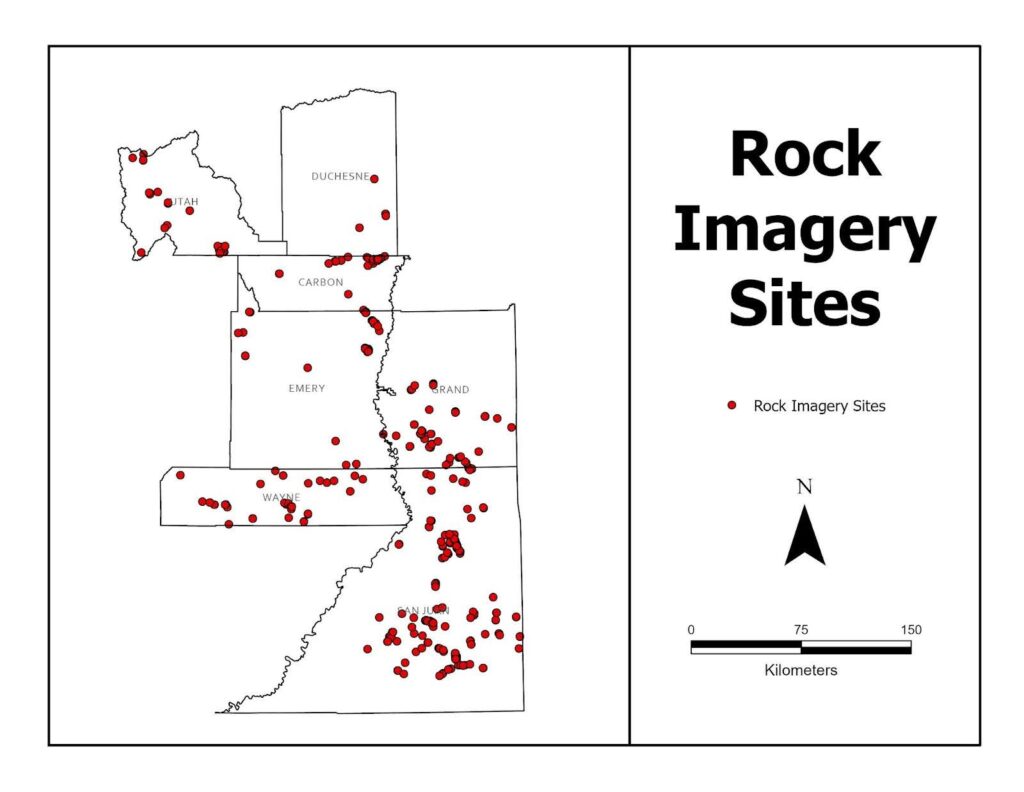

The project began with a file search through all archaeological site forms mentioning rock imagery within the Eastern Utah counties of Duchesne, Carbon, Grand, Emery, San Juan, Utah, and Wayne; the goal was to identify “round things” in site photographs and decide whether these figures may represent shields.

The primary factors in determining whether a “round thing” was likely a shield figure was the presence of an anthropomorph interacting with the figure (establishing size and utility) or the presence of adornments reflective of the influence of gravity or similar to those seen on physical shields (Figure 6).

These shield figures were then categorized by type: circles, spirals, shield bearers, or indeterminate round. Circles were defined as any clearly round figure, while spirals were defined as figures with a single curvilinear element with a clear start and end point. Sites in the indeterminate group had round rock imagery elements that may represent shields but could also represent another circular object, like the Sun. (Examples of figures classified as shields for this project can be seen in Figures 3 – 7). If no such figures were identified, the absence was noted.

Shield figures were categorized into four types: circles, spirals, shield bearers, or indeterminate round.

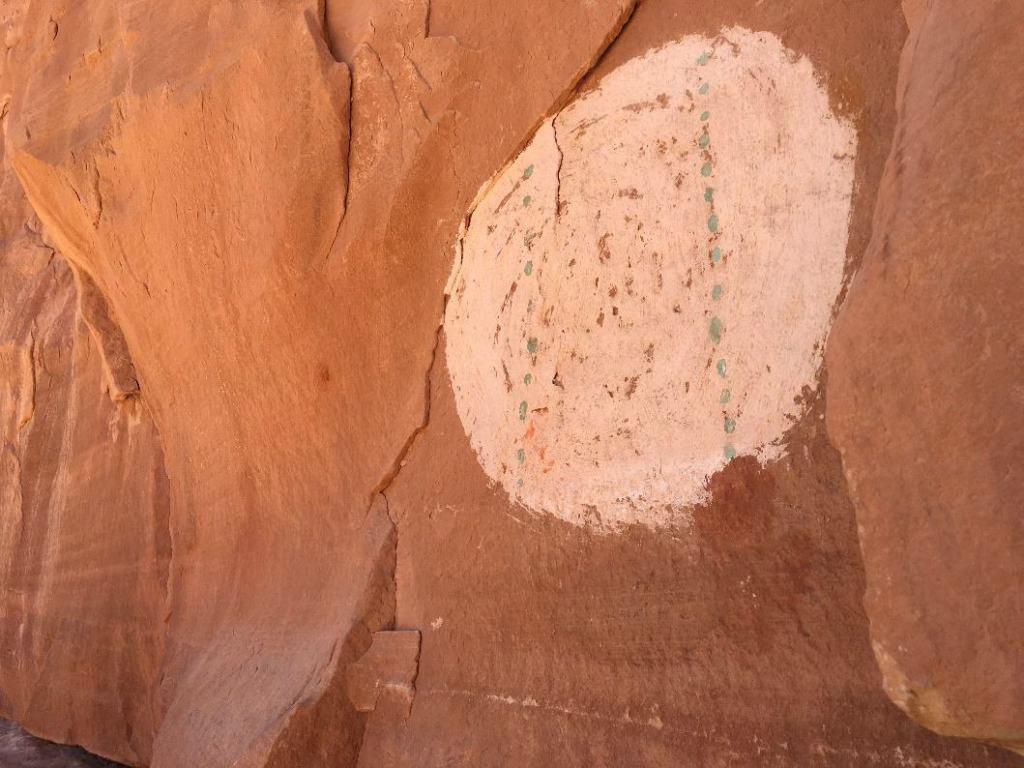

Figure 3. Ancestral Puebloan shield pictograph from San Juan County, Utah.

Figure 4. Fremont shield bearer petroglyph (with spiral shield) from Emery County, Utah.

Figure 5. Circular shield petroglyph from Emery County, Utah.

Figure 6. Fremont shield bearer petroglyph from Emery County, Utah.

Figure 7. Spiral shield petroglyph from San Juan County, Utah.

Once the site forms had been searched, analysis of the spatial distribution of shield figures began; this took place in ArcGIS Pro, a software that helps manipulate, analyze, and visualize spatial data.

Results

In total, there were 473 rock imagery site forms searched (these sites can be seen in Figure 8). Of these, it was determined that 151 sites had possible shield figures: 119 of these sites had circle(s), 59 had spiral(s), 27 had shield bearer(s), and one had indeterminate round figures (due to the extremely small sample size, this site was left out of future analysis).

Out of 473 rock imagery sites, 151 had shield figures.

In some cases, sites had multiple kinds of shield figures: 35 had circle(s) and spiral(s), nine had shield bearer(s) and circle(s), five had circle(s), spiral(s), and shield bearer(s), and one had shield bearer(s) and spiral(s). These sites were counted for each type of figure in the analysis.

Figure 8. Spatial distribution of rock imagery sites in Eastern Utah.

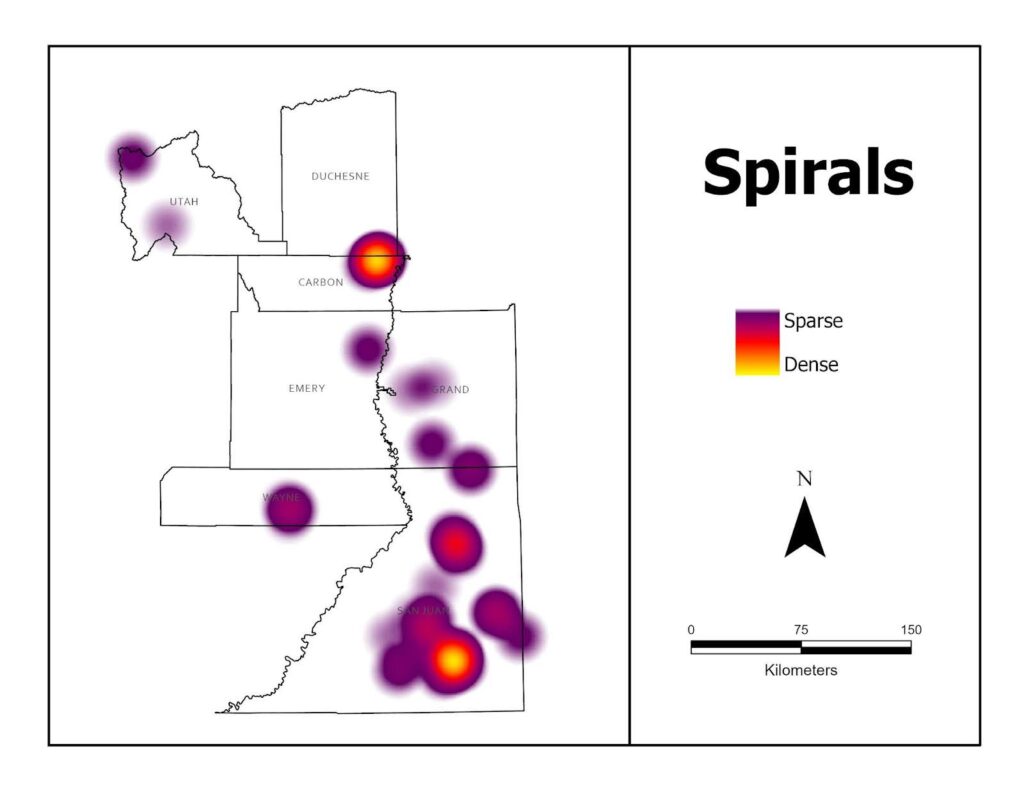

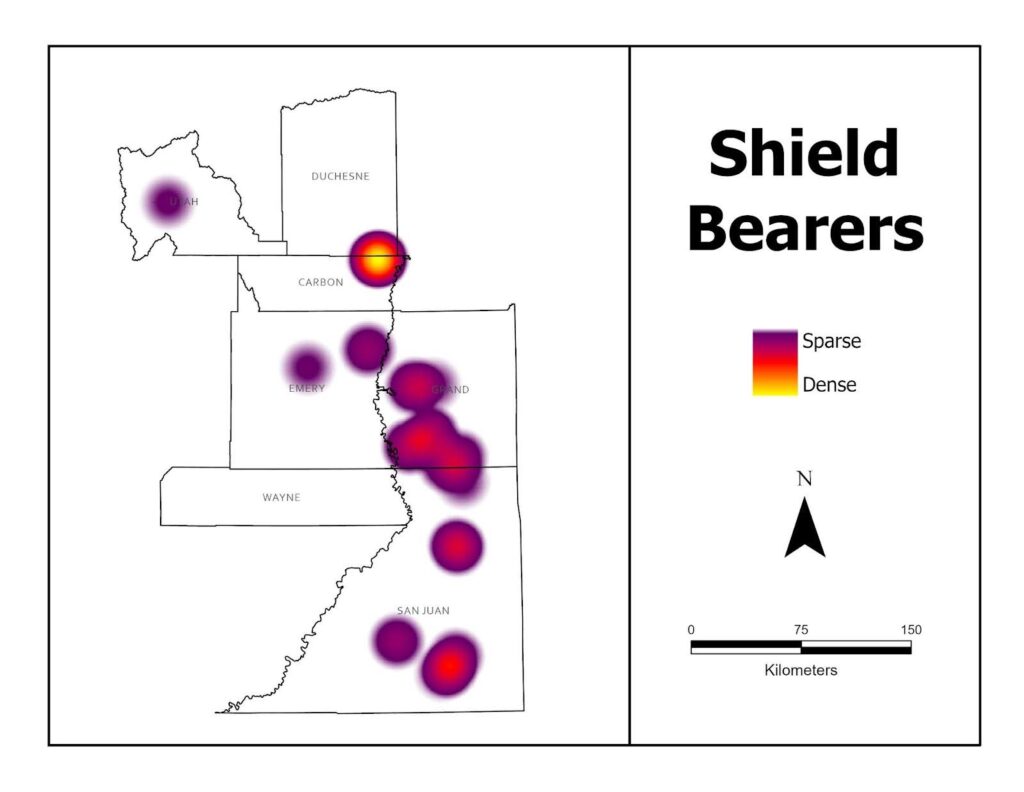

By producing heat maps showing the density of shield imagery distribution (Figures 9-11), some spatial patterns were identified.

Figure 9. Spatial distribution of circle shield figures in Eastern Utah. Warm (yellow-to-red) areas indicate a cluster of sites with such figures. Cooler (purple-to-indigo) areas indicate regions with fewer (1-3) relevant sites.

Figure 10. Spatial distribution of spiral shield figures in Eastern Utah.

Figure 11. Spatial distribution of shield bearer figures in Eastern Utah.

Notably, shield iconography seems to be concentrated along the eastern side of the Green River (the majority of the river closely follows the eastern boundaries of Carbon and Emery counties) and the most prominent hotspots are located in Carbon County and San Juan County. For all types of shield imagery (circles, spirals, and shield bearers) a large and significant hotspot occurs in Nine Mile Canyon in Carbon County, Utah; Nine Mile Canyon is often referred to as the “world’s longest art gallery” and the concentration of shield imagery here is not much of a surprise.

A hotspot for spiral shield figures exists in the southern part of San Juan County. Hotspots for shield bearer figures are present throughout Grand County, loosely following the path of the Green River.

More interestingly, a significant hotspot for sites with spiral shield figures exists in the southern part of San Juan County; this hotspot is not nearly as pronounced when looking at circle shield figures or shield bearers. The distribution of shield bearers presents another compelling pattern; unlike circles and spiral figures, hotspots for shield bearers also occur in Grand County, loosely following the path of the Green River.

Future research may provide insight into why these patterns exist.

Discussion

These results provide a preliminary insight into the distribution of shield iconography in Eastern Utah; however, there is more to be done in order to fully understand the implications of these results.

To start, the locations of other features surrounding shield imagery may provide additional clues as to why these images were left behind in the places that they were. Questions such as “Are shield figures more often to be found associated with long-term residential sites than other site types?” and “Are shield figures found in a specific geographic context, such as near a river?” are ones that might provide a more detailed and meaningful analysis. In addition, asking the question of what types of shield imagery are associated with certain past peoples/cultures could provide an avenue towards deepening our understanding of these people. (Currently, dating of rock imagery is largely not possible. If reliable relative or absolute dating techniques are developed in the future, this question might become easier to answer.)

Further, changes in the way the current analysis was made could also influence the results. Currently, the frequency of shield figures is measured by site, meaning that each site is counted once for each type of shield iconography present; however, in many cases, each site has multiple shield figures, often of the same type. How would counting each figure as separate from its associated site impact the results?

Conclusion

Archaeologists are often hesitant to use rock imagery for research as the risk of subjectivity and the temptation to interpret figures or sites is large. However, when re-examining rock imagery in a different scientific context, as this project attempts to accomplish, avenues for rock imagery research can be discovered.

Resources

Jolie, E. A. (2022). Basketry Shields of the Prehispanic Southwest. KIVA, 88(4), 453–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2022.2086400

Loendorf, L. L., & Conner S. W. (1993). The Pectol Shields and the Shield-Bearing Warrior Rock Art Motif. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 15(2), 216-224. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27825520