By Tiffany Tuttle Collins, archaeologist at SWCA Environmental Consultants, Inc.

If there’s one thing an archaeologist loves, it’s trash. Trash gives us the unvarnished truth about the lives of past people. Written accounts may omit unflattering details and photographs may be staged, but good old garbage is unflinchingly honest. Just think about the last thing you threw in the trash – what do you think that would say about where you live, how old you are, or even the things you enjoy? Trash is the archaeologists’ truth serum.

So of course archaeologists were thrilled to find a cache of trash in downtown Salt Lake City! In November 2020, as the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) was completing their new Central Bus Operations and Maintenance Facility in downtown Salt Lake City, they found a surprise. While digging a utility trench, workers uncovered two sets of railroad tracks and a pile of trash 3 ½ feet below ground. This trash pit was so old, it dated to before Utah was even a state.

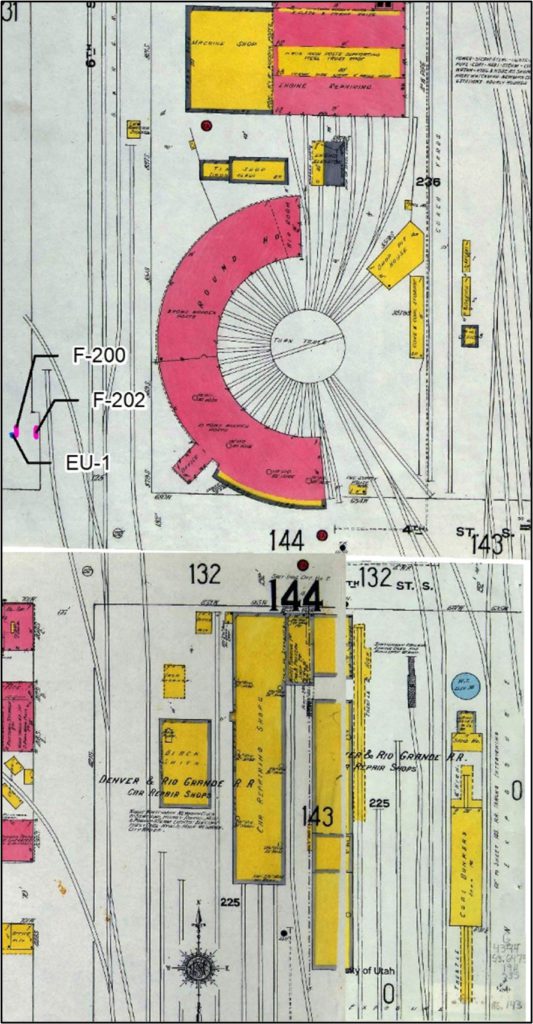

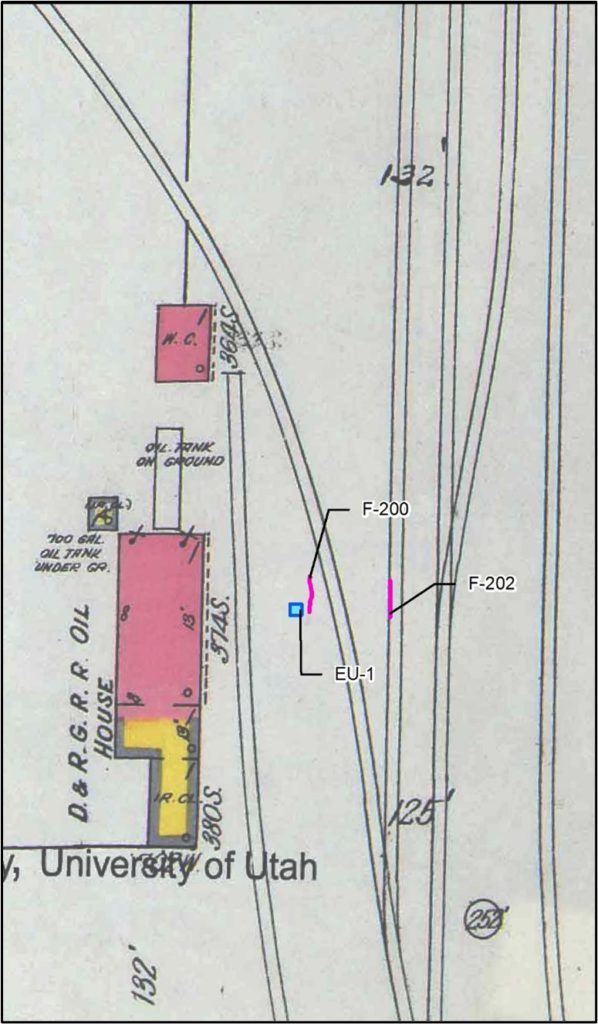

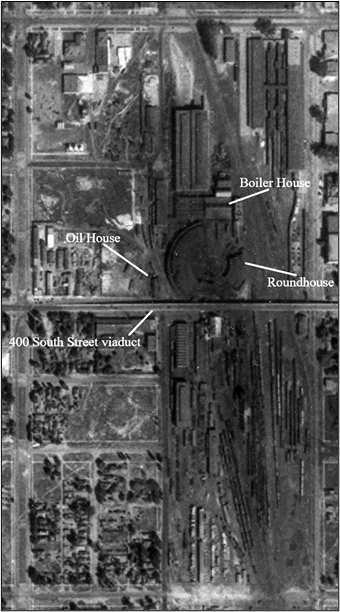

That fall in 2020, the UTA was working in the old Denver & Rio Grande Western (D&RGW) rail yard dates back to 1882, so they expected to find old rails and the odd piece of machinery. UTA hired SWCA Environmental Consultants (SWCA) to excavate and research a variety of buildings and artifacts that came from the original railroad. Things like repair shops, standard gauge rail lines, and blacksmith shops were all expected based on historical maps and photographs, and the archaeologists at SWCA were able to relocate these large features and document them.

Historic maps showed that the buried tracks were next to the D&RGW’s oil house. Oils were necessary to lubricate all kinds of train engine parts, but because of their flammability, they were stored a little ways from the main maintenance facility. The buried railroad tracks ran right in front of the oil house for deliveries.

The historical D&RGW rail yard had been between 600 and 700 West, and that’s where the archaeologists focused much of their attention in earlier stages of the project. They were surprised, however, when construction workers digging a utility trench outside of this zone, in an area west of 700 West, accidentally revealed the two sets of tracks. The buried tracks were narrow-gauge, and archaeologists knew that the D&RGW converted all its tracks to standard-gauge width in 1890. The fact that archaeologists found narrow gauge rails provided an end-date to the use of those tracks. But no one expected to find an enormous trash pile – essentially a time capsule from the 1890s!

The tracks were raised at least 2 ½ feet above ground on concrete foundations, and trash seems to have been tossed into a pile up against the foundation. Was there a maintenance pit here for train cars and engines, similar to a Jiffy Lube bay? Hard to tell, but it seems like once the old rails were abandoned in 1890, this became a perfect place to throw trash.

Let’s Talk Trash!

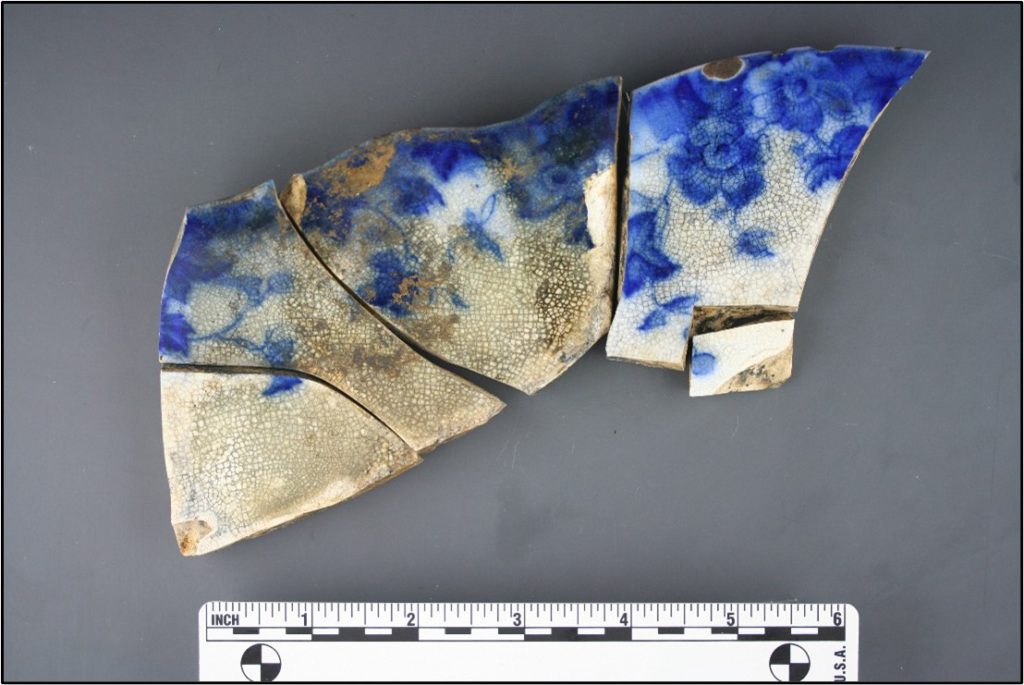

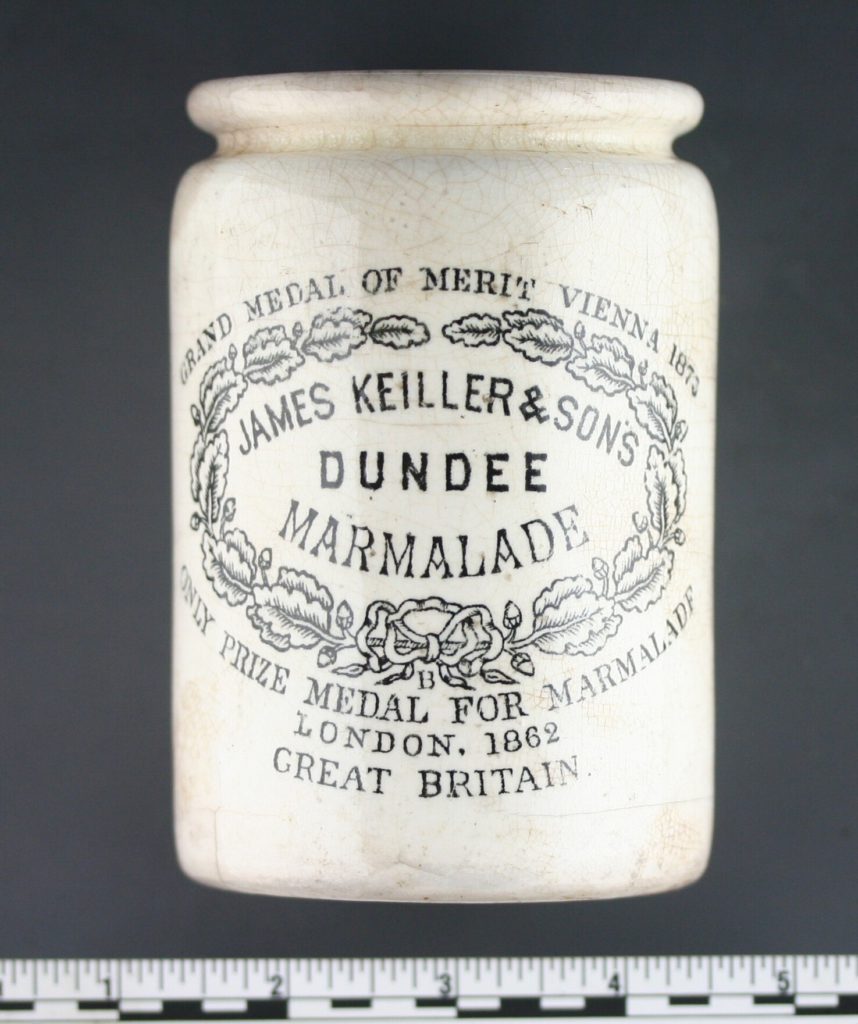

SWCA excavated a section of the trash pile and collected almost 9,500 artifacts. Eighty-five percent were bottles—soda water and snake-oil medicines, shoe polish and cold cream jars, and beer and milk bottles. There were lots of ceramics too, including a marmalade crock; broken dinner plates, serving platters, and porcelain teacups; and pieces of toilet rim with hand-painted gold decoration. There were steak and chicken bones, along with scraps of metal, wood furniture, and leather.

For almost ten thousand artifacts, that’s not a lot of variety! What could bring these dining-related pieces of trash to in an abandoned railyard?

Archaeologists suspect that most of the trash came from dining cars, where upper-class passengers could get chef-cooked meals, and from repairs to the D&RGW’s luxurious Pullman sleeping cars. Ceramic dinnerware, like the examples pictured above, would have oozed elegance and let passengers know that they were getting their money’s worth from the journey! But broken ceramic plates don’t look quite as elegant, so anything more than a chip would doom the vessel to the trash heap.

In the days before curbside recycling, it was often easier to throw glass bottles in the garbage, too. Glass bottles, like these above, made up most of this trash dump. Single use by design, it’s no wonder that this dump contained so much glass. Although very few bottles were unbroken, archaeologists were able to learn a lot from the fragments. Click on the images to open them in a new tab and examine them for yourself!

Archaeologists also discovered items of a more personal nature. From durable pieces of clothing, like buttons and shoe leather, to shoe polish and cold cream, this dump tells us a lot about the people who rode the rails and worked at the rail yard. After an overnight journey, people (especially women) wanted to make sure they arrived at their destination feeling fresh and looking their best. The shoe polish and cold cream may have been left behind or discarded by passengers at Salt Lake City, and these items found their way into the dump. Items of clothing like buttons and shoes may have been lost by passengers, or may have been discarded by workers as they went about their duties in the rail yard.

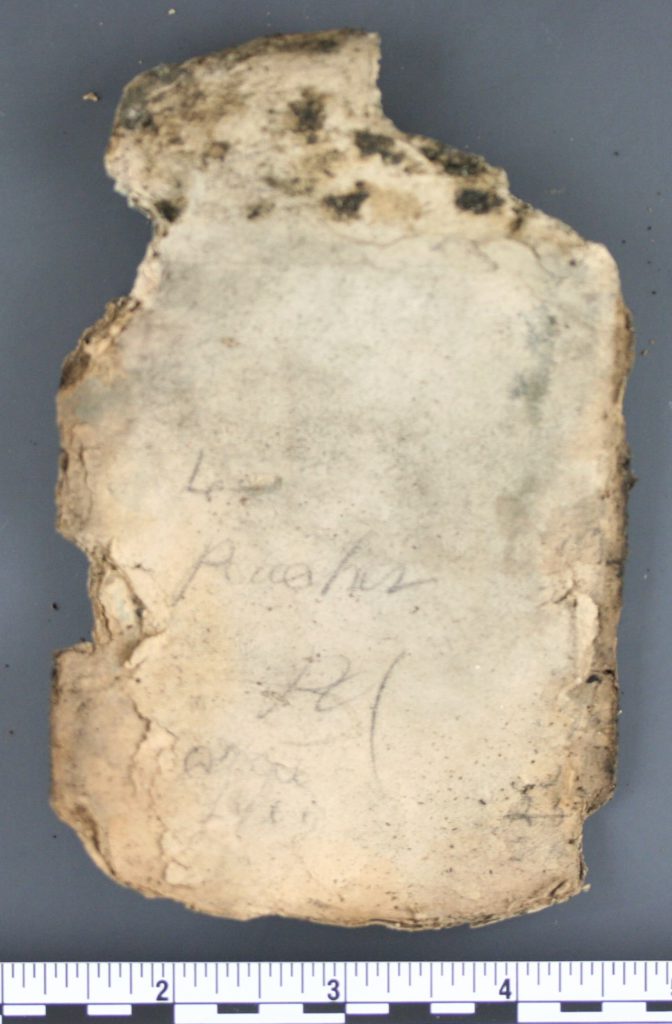

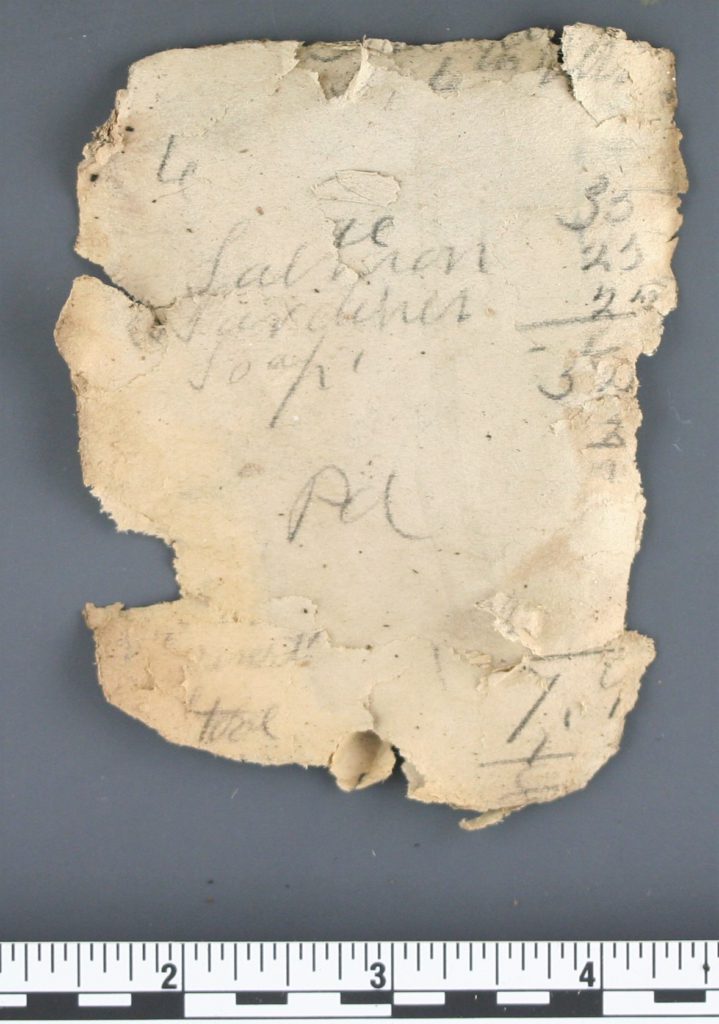

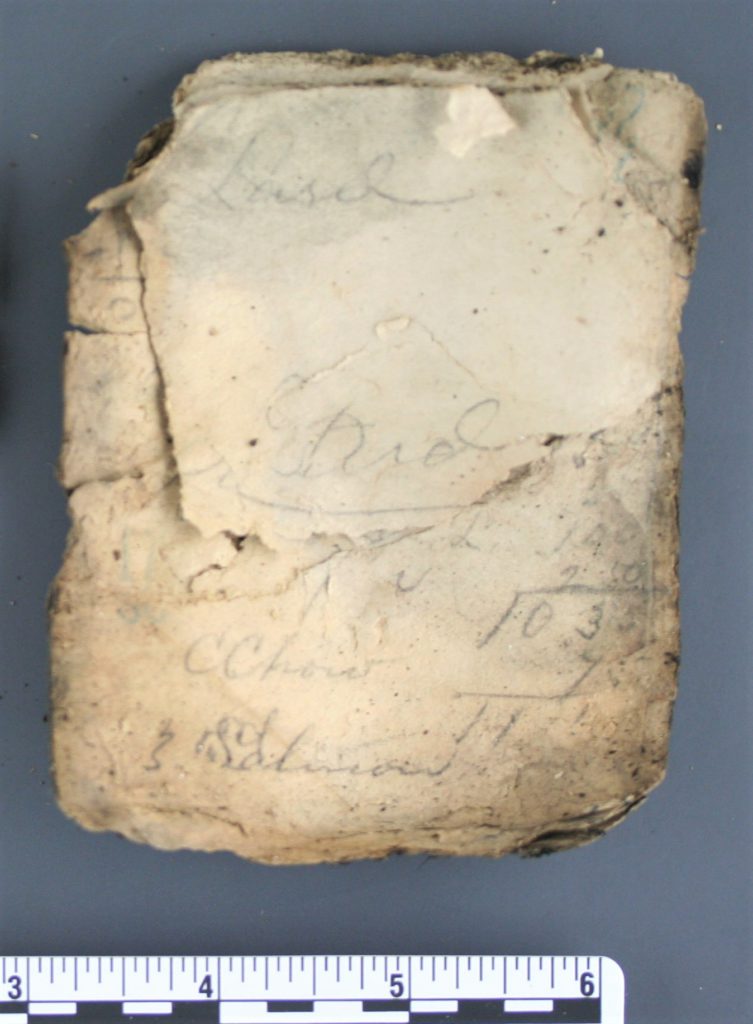

But near the bottom of the pile there were hand-written ledgers, a rare find since paper decays so quickly. Only a few pages are legible, but the penciled notes look like receipts, listing canned sardines, peaches, cooking lard, and soap. Click on the images to see what you can make out! Interestingly, no cans were mixed in with the trash, so perhaps these are grocery receipts from the working-class and immigrant rail yard employees.

What Does This All Mean?

Archaeologists surmise, based on the ages of the artifacts, that the trash pile was used from around 1890 until at least 1912, and maybe as late as 1929. Then it was buried and forgotten, inadvertently creating a snapshot of railroad life that is rarely recorded in written history. These artifacts tell stories of people who were living a life of luxury on the Pullman cars, eating meat off of fine dinnerware and taking care of their bodies and their clothing while on their trip. It also tells the story of the people who had to clean out and repair those cars and engines, who determined that an abandoned section of rail yard would be a convenient place to dump their trash.

Over a century later, this accidental time capsule had been completely forgotten under our feet, just west of downtown Salt Lake City! Archaeology provides a window to the past, and it’s the most intriguing when you find these windows in the places you didn’t expect!

Do you have any personal or family stories from the heyday or rail travel? Let us know on social media, we would love to hear all about it!