Andrew Ugan, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sacramento District.

This blog is a part of an agreement under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act to highlight the history of this resource in Salt Lake County, pursuant to federal laws. The SHPO works collaboratively with dozens of state and federal agencies on projects that intersect with significant resources like the Surplus Canal. Our mission is to shed light on the rich historical tapestry surrounding the Surplus Canal.

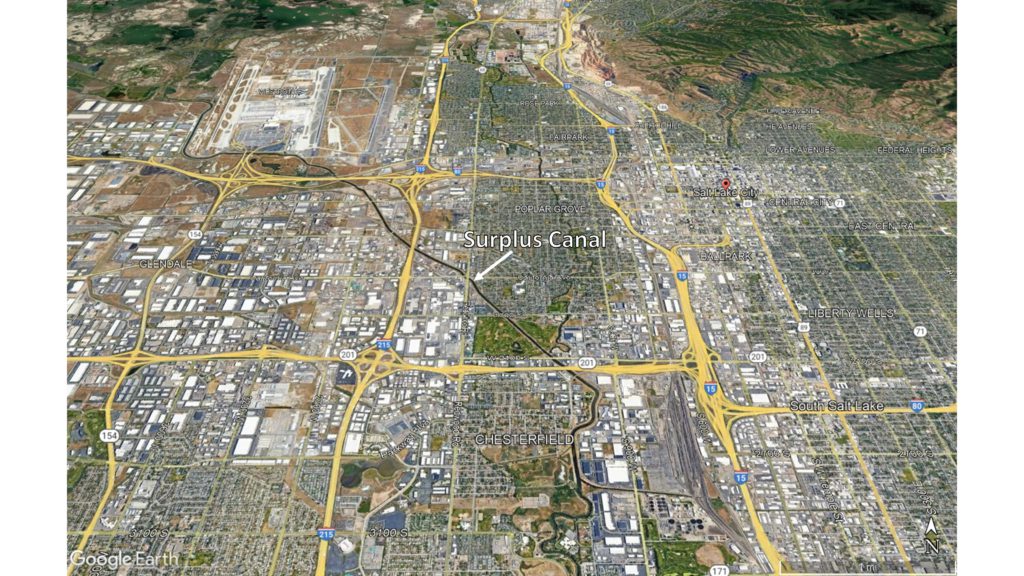

The Jordan and Salt Lake Surplus Canal (Surplus Canal; Figure 1) plays an important role in reducing flood risks in Salt Lake City and Salt Lake County. The Jordan and Salt Lake Surplus Canal Company first built the canal in 1885. At the time, it extended from the Jordan River near 12th St in Salt Lake City, Utah (now 2100 S) northwest to the Cohn Ranch property (located just east of the Salt Lake International airport; Salt Lake Herald 1896 Nov. 18:8).

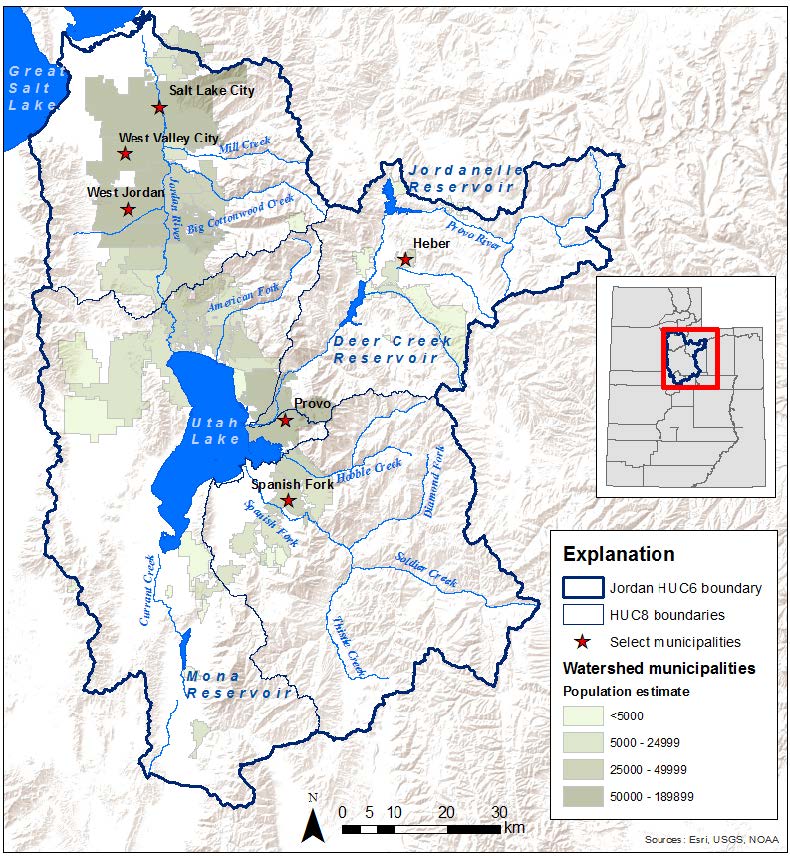

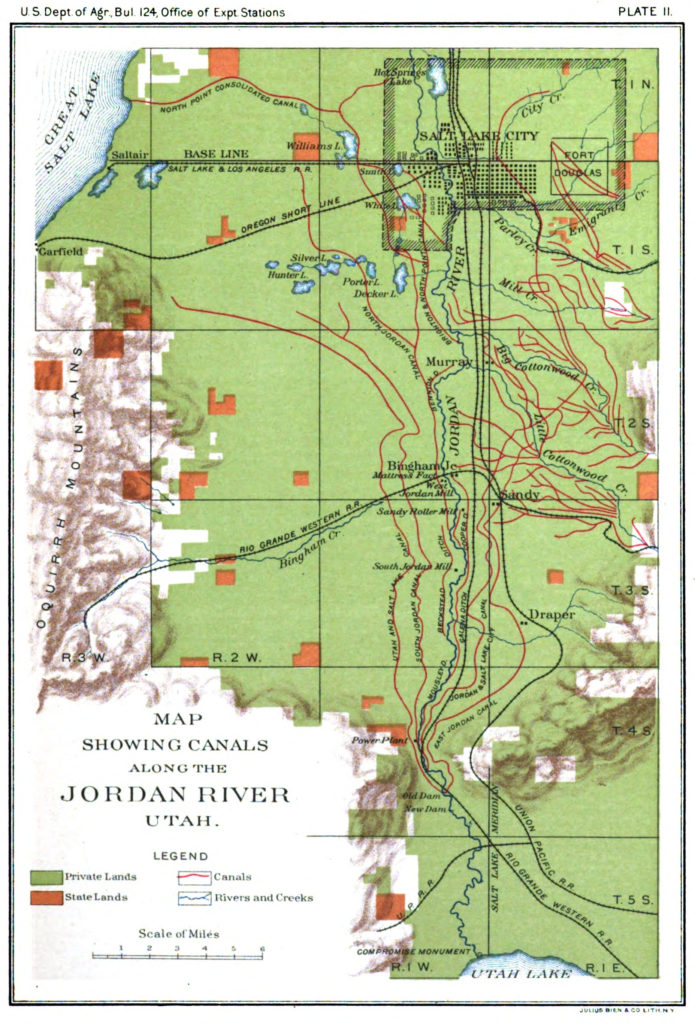

The canal was needed to control flooding on the Jordan River and remove irrigation seepage from adjacent lands (Mead 1904: 47; The Salt Lake Herald 1885 March 8: 12; The Salt Lake Herald 1885 March 9: 4). The Jordan River drains a 3800-square-mile watershed (Figure 2). Waters from Utah and portions of Juab, Sanpete, and Wasatch counties collect in Utah Lake before overflowing at the lake’s north end and continuing down the Jordan River. The river then picks up additional waters from Little Cottonwood Creek, Big Cottonwood Creek, Mill Creek, Parley’s Creek, Emigration Creek, Red Butte Creek and City Creek as it flows through the Salt Lake Valley. In wet years, the added input from the creeks in Salt Lake Valley caused the river to overflow its banks, flooding low-lying settlements around Salt Lake City. Construction of the Surplus Canal was meant to alleviate this problem by diverting water from the Jordan River beginning just downstream from the confluence with Mill Creek, reducing flow in the main channel through the city.

In 1896 the Salt Lake City Engineer described the early canal as having had a bottom width of 40 feet with a depth of 4.5 feet below the Jordan River high water (Salt Lake Herald 1896 Nov. 18:8). It was estimated to provide a capacity of 500 cubic feet per second, but reductions in width, bridges, and obstructions may have resulted in a final capacity 30% lower. Crossing was originally limited to a single bridge, and overflows from the canal reportedly damaged or degraded roads nearby (Salt Lake Evening Democrat 1885 June 29:4). The original canal terminated at the Cohn Ranch, and Cohn would subsequently threaten to sue for flooding caused on his land.

On May 21, 1886, the Jordan and Salt Lake Surplus Water Canal Company entered into an agreement to complete the Surplus Canal from Cohn’s Ranch to the Great Salt Lake. The company had run into financial difficulties early on, however (Salt Lake Evening Democrat 1885 June 29:4; Salt Lake Herald 1885 July 26: 4), and never completed this final portion of the canal. The company sought assistance from outside sources, including both Salt Lake City and County (e.g., Salt Lake Herald 1885 Apr 1: 4). On December 3, 1886, the Surplus Canal was deeded to them, with the caveat that the City and County keep the canal open and in good repair for a period of 10 years (Salt Lake Herald 1889 Dec 15: 3).

There were early plans by Salt Lake City to use the Surplus Canal for sewage disposal, but the cost of pumping waste to the canal initially proved prohibitive (Salt Lake Herald 1888 Aug 25:1). Within a few years, however, an initial sewage system was built. The city began pumping sewage into the Surplus Canal (Salt Lake Herald 1890 May 25:3; Salt Lake Herald 1892 Aug 13:8; Salt Lake Herald 1893 Mar 04:5), much to the consternation of nearby landowners. Both the Surplus Canal and the Jordan River would continue to receive sewage from Salt Lake City until completion of the five-mile Outlet Canal from the gravity sewer to the Great Salt Lake on November 10, 1911 (Cater 2014; SLCDocs 2000).

While the Surplus canal was not constructed as a source of irrigation water, the North Point Consolidated Irrigation Company (North Point) did have an agreement to pull water from the Surplus Canal for this purpose. However, the Surplus Canal would also carry irrigation run-off delivered by nearby canal systems. This run-off was so laden with alkali salts that it rendered the water downstream unsuitable for irrigation, leading to a lengthy legal dispute between North Point, the City and County of Salt Lake (who managed the Surplus Canal), and the various other canal companies polluting the water with their irrigation run-off. This case would eventually be resolved in favor of North Point in 1898 after an appeal to the Utah Supreme Court (Salt Lake Herald 1898 Feb 06:8, June 07:6). However, even as late as 1904 no substantial irrigated agriculture was taking place. Although the North Point Canal connected with the Surplus Canal and served a large area of land between Salt Lake City and the lake (Figure 3), the Surplus and North Point Canals remained minor irrigation works. Very little of the land was improved, as it remained too strongly alkaline to be farmed successfully using the methods of the time (Mead 1904: 47).

Heavy flooding in early 1896 once again inundated low-lying areas of Salt Lake City near the Jordan River. The city council responded by instructing the city engineer to study improving the Surplus Canal to help prevent future flooding (Salt Lake Herald 1896 June 17:8). Following the engineer’s report, the council would approve extending the canal to the Great Salt Lake and increasing its bottom width to 60 feet (Salt Lake Herald 1896 Dec 2:8), with Salt Lake County paying half. These improvements were later postponed due to County concerns over the potential need for other, additional modifications to the canal and ongoing legal conflicts with North Point Consolidated Irrigation Co. (Salt Lake Herald 1897 Jan 6: 3). As a consequence, the Surplus Canal would operate with minimal maintenance for another decade.

In 1909, heavy flooding once again struck Salt Lake City (Salt Lake Herald 1909 June 10: 1; 1909 June 11:1-2). By that year, the Surplus Canal was estimated to be carrying 25% or less of its original design flows (Figure 4), and its repair became a critical concern. This time action came swiftly, and by 1910 the city and county had hired a dredger to start expanding the canal (The Herald-Republican 1910 Feb 23:2;). When work began, the Surplus Canal was described as little more than a depression in the ground in places. Dredging started under a contract to use the Utah Sand, Dredging, & Construction Co. dredger (Figure 5), which was later replaced by a dredger purchased and owned by Salt Lake City (The Salt Lake Tribune 1910 Oct 21: 14). By the time work was complete, the canal would be at least 60 feet wide at the base and at least six feet deep over most of its length (The Salt Lake Tribune 1911 Feb 23:3; 1911 Mar 05:1,14).

Work and maintenance on the canal continued over the coming years (Figure 6), but continued concerns over flooding eventually led local authorities to reach out to the federal government for assistance. Congress responded by authorizing a preliminary examination of regional flood control needs on June 28, 1938, followed by a study under the direction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE, 1939). This study culminated in congressional authorization for the Jordan River Project on July 24, 1946, with execution of the project beginning in 1959 (USACE 1961).

Working with Salt Lake County, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project would replace the control structures of the Jordan River and Surplus Canal where they bifurcated at 2100 South, improve the channel of the Jordan River and levees from 2100 S to Mill Creek, improve the channel and levees of the Surplus Canal from 2100 S to the Goggin Drain, and provide for structural changes to bridges and other utilities (USACE 1961; Figure 7). Per the Design Memorandum (USACE 1957):

The Surplus Canal channel will be improved by means of widening, deepening, and minor realignment for a total distance of 35, 300 feet from its beginning near 21st South Street downstream to Goggin Drain. Excavated materials, which will amount to about 635,000 cubic yards, will be placed in parallel levees on each side of the canal and located to provide a 20-foot berm between the toe of the levee and the canal bank.

Most of this work was executed under contract with Thorn Construction Company between September 1959 and October 1960.

The Salt Lake County Department of Civil Works has continued to maintain and upgrade the canal since that time, including a substantial realignment of the canal’s northern extent to accommodate expansion of the Salt Lake International Airport in the early 1990’s, as well as replacing the Jordan River diversion structure again in 1998 (USACE 1961, design update). While the canal no longer resembles the structure first built in 1885, or even that built by USACE in 1959, it continues to form an important part of the overall flood risk management system in Salt Lake County.

References

Cater, Ben (2014). Segregating Sanitation in Salt Lake City, 1870-1915. Utah State Historical Quarterly, 82(2): 92-113.

Mead, Elwood (1904). Irrigation Investigations in Utah. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Office of Experiment Stations Bulletin No. 124. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Menuz, Diane, and Ryhan Sempler (2018). Jordan River Watershed Wetland Assessment and Analysis. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey.

Salt Lake Evening Democrat (1885 June 29). Laborers Who Should Be Paid; A Dangerous Stream to Cross.

The Salt Lake Herald (1885 March 8). An Incorporation Scheme.

The Salt Lake Herald (1885 March 9). The Drainage Canal.

Salt Lake Herald (1885 April 1). The Council of Twelve, Important Business Comes Up for the Consideration of the City Fathers.

Salt Lake Herald (1885 July 26). No Headline. Article at base of column two.

Salt Lake Herald (1896 November 18). That Surplus Canal.

Salt Lake Herald (1888 August 25). Sewerage Question.